Jackson remembered as champion for civil rights

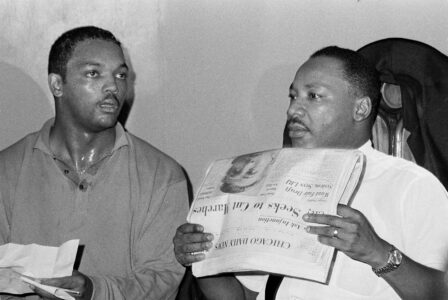

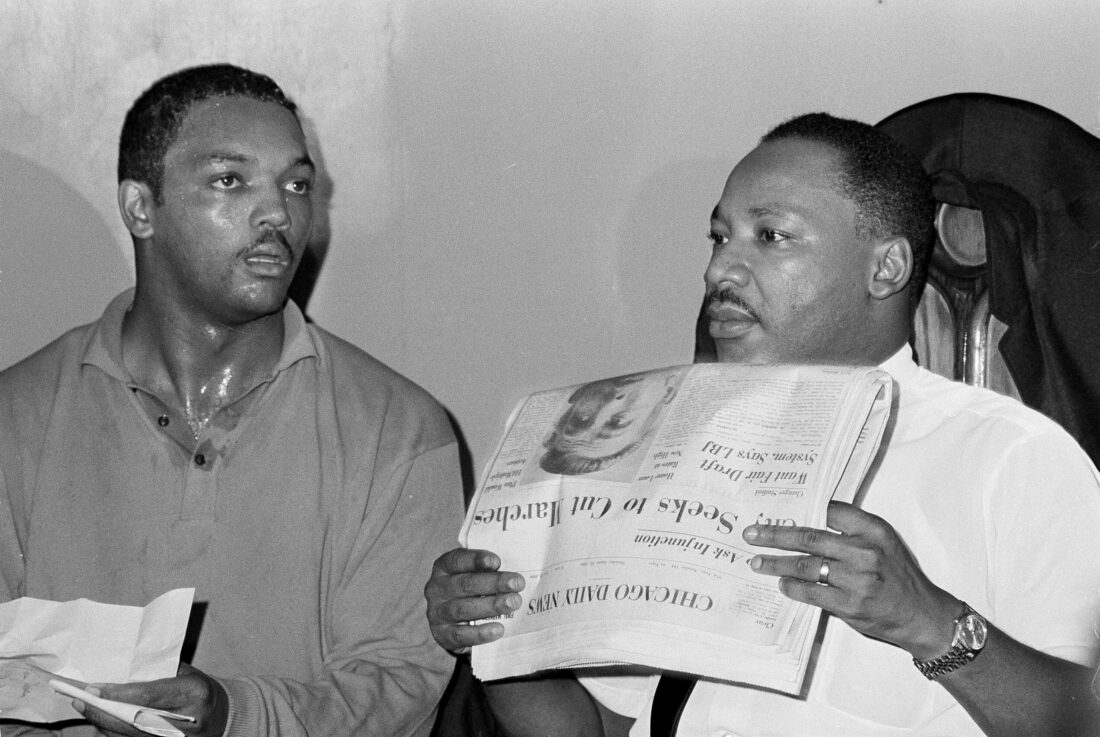

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., right, and his aide Rev. Jesse Jackson are seen in Chicago, Aug. 19, 1966. (AP Photo/Larry Stoddard, file)

CHICAGO (AP) — From the moment the Rev. Jesse Jackson stepped forward as torchbearer to what was then a largely Southern civil rights struggle — a movement with much unfinished business — he created a bridge.

From the South’s fight with Jim Crow to the North’s battle with systemic racial inequality, from the buttoned-up, conservative generation of King’s circle to the dashiki-wearing Black Power leaders and the activists of the hip-hop generation, Jackson forged a link between improbable dreams and political power.

“From Martin Luther King to Barack Obama, there’s a bridge called Jesse Jackson,” the Rev. Al Sharpton said.

Jackson, a protégé of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. who led the Civil Rights Movement for decades after the revered leader’s assassination, died on Tuesday, his family said. He was 84.

Jackson kept up his public advocacy for racial justice, economic and political inclusion, and civil and human rights for more than a half-century, even after a neurological disorder in his later years affected his ability to move and speak.

Weighing in on political events, supporting the families of Black Americans killed by police and participating in COVID-19 vaccination drives to battle hesitancy in Black communities, Jackson built on a career that included running for president, international diplomacy and influencing the lexicon of racial identity in America.

Jackson clearly wasn’t the lion he had been toward the end, but his presence at racial justice protests and COVID-19 advocacy events, and his arrest outside the U.S. Capitol while calling on Congress to end the filibuster to protect voting rights displayed the bite left in his bark.

“We’ve always had a place for him,” said the Rev. William Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign and one of many activists who have followed in his footsteps. Jackson urged them to “live life so that it’s not your alarm clock that awakes you in the morning, but a purpose. … A purpose will get you up when you want to stay down.”

At George Floyd’s memorial service, Jackson’s plaintive call, “I can’t breathe!” pierced the collective silence in a Minneapolis cathedral. He cried out twice more as the minutes ticked by to symbolize how long Floyd had a police officer’s knee pressed on his neck.

It was not only Jackson’s powerful expression of his own grief over Floyd’s death, which sparked global protests against racial injustice. It was a reminder that his voice still carried the singular resonance that for decades made him an international figure for civil and human rights.

Jackson returned to rally demonstrators marching through downtown Minneapolis, and stood with Floyd’s family when a jury convicted former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin of murder in Floyd’s death. “Even if we win,” he told the marchers, “it’s relief, not victory. They’re still killing our people. Stop the violence, save the children. Keep hope alive.”

“I think the fact that he came and then came back for the judge’s verdict, suffering with Parkinson’s, shows the determination that Jesse Jackson had all the way to the end,” Sharpton said about his longtime mentor. “He once said to me, years before he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, ‘I’m not going to stop until I drop. I’m going to die on the battlefield.'”