Payout after Maduro’s capture puts prediction markets in the spotlight

The Polymarket prediction market website is seen on a computer screen, Sunday, in New York. (AP Photo/Wyatte Grantham-Philips)

Prediction markets let people wager on anything from a basketball game to the outcome of a presidential election — and recently, the downfall of former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

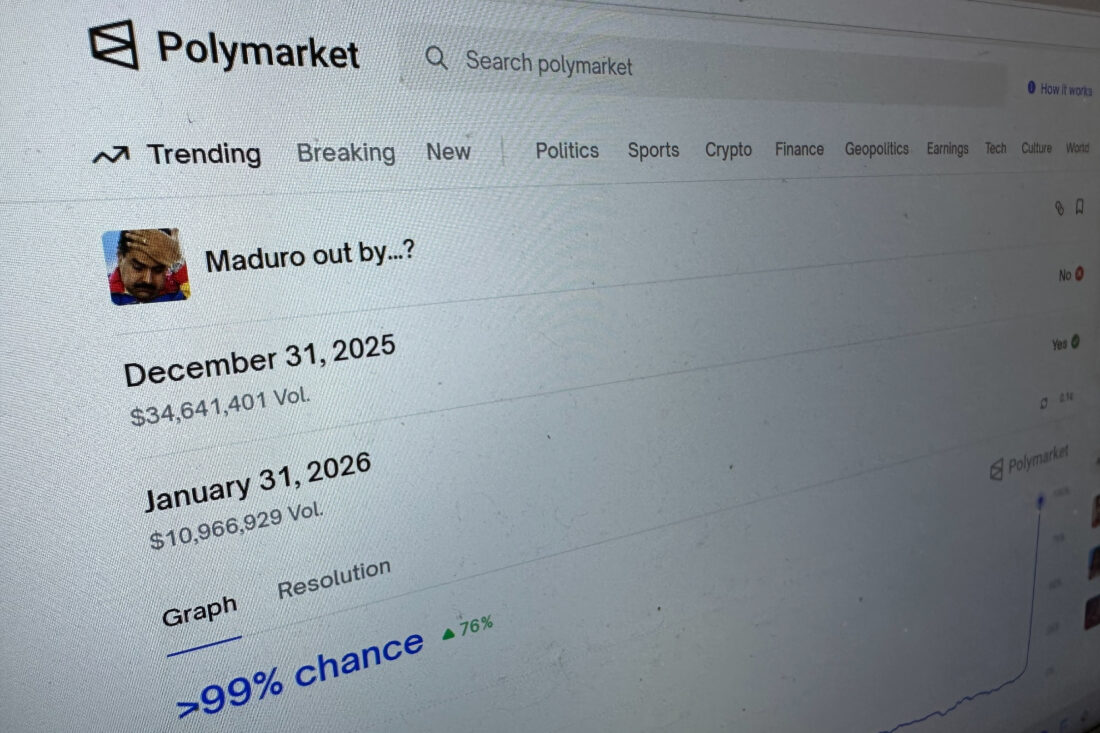

The latter is drawing renewed scrutiny into this murky world of speculative, 24/7 transactions. Last week, an anonymous trader pocketed more than $400,000 after betting that Maduro would soon be out of office.

The bulk of the trader’s bids on the platform Polymarket were made mere hours before President Donald Trump announced the surprise nighttime raid that led to Maduro’s capture, fueling online suspicions of potential insider trading because of the timing of the wagers and the trader’s narrow activity on the platform. Others argued that the risk of getting caught was too big, and that previous speculation about Maduro’s future could have led to such transactions.

Polymarket did not respond to requests for comment.

The commercial use of prediction markets has skyrocketed in recent years, opening the door for people to wage their money on the likelihood of a growing list of future events. But despite some eye-catching windfalls, traders still lose money everyday. And in terms of government oversight in the U.S., the trades are categorized differently than traditional forms of gambling — raising questions about transparency and risk.The scope of topics involved in prediction markets can range immensely — from escalation in geopolitical conflicts, to pop culture moments and even the fate of conspiracy theories. Recently, there’s been a surge of wages on elections and sports games. But some users have also bet millions on things like a rumored — and ultimately unrealized — “secret finale” for the Netflix’s “Stranger Things,” whether the U.S. government will confirm the existence of extraterrestrial life and how much billionaire Elon Musk might post on social media this month.

In industry-speak, what someone buys or sells in a prediction market is called an “event contract.” They’re typically advertised as “yes” or “no” wagers. And the price of one fluctuates between $0 and $1, reflecting what traders are collectively willing to pay based on a 0% to 100% chance of whether they think an event will occur.

The more likely traders think an event will occur, the more expensive that contract will become. And as those odds change over time, users can cash out early to make incremental profits, or try to avoid higher losses on what they’ve already invested.

Proponents of prediction markets argue putting money on the line leads to better forecasts.

Polymarket is one of the largest prediction markets in the world, where its users can fund event contracts through cryptocurrency, debit or credit cards and bank transfers.

Restrictions vary by country, but in the U.S., the reach of these markets has expanded rapidly over recent years, coinciding with shifting policies out of Washington. Former President Joe Biden was aggressive in cracking down on prediction markets and following a 2022 settlement with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Polymarket was barred from operating in the country.

That changed under Trump late last year, when Polymarket announced it would be returning to the U.S. after receiving clearance from the commission. American-based users can now join a platform “waitlist.”

Meanwhile, Polymarket’s top competitor, Kalshi, has been a federally-regulated exchange since 2020. The platform offers similar ways to buy and sell event contracts as Polymarket — and it currently allows event contracts on elections and sports nationwide. Kalshi won court approval just weeks before the 2024 election to let Americans put money on upcoming political races and began to host sports trading about a year ago.