Artifacts provide clues on early people in region

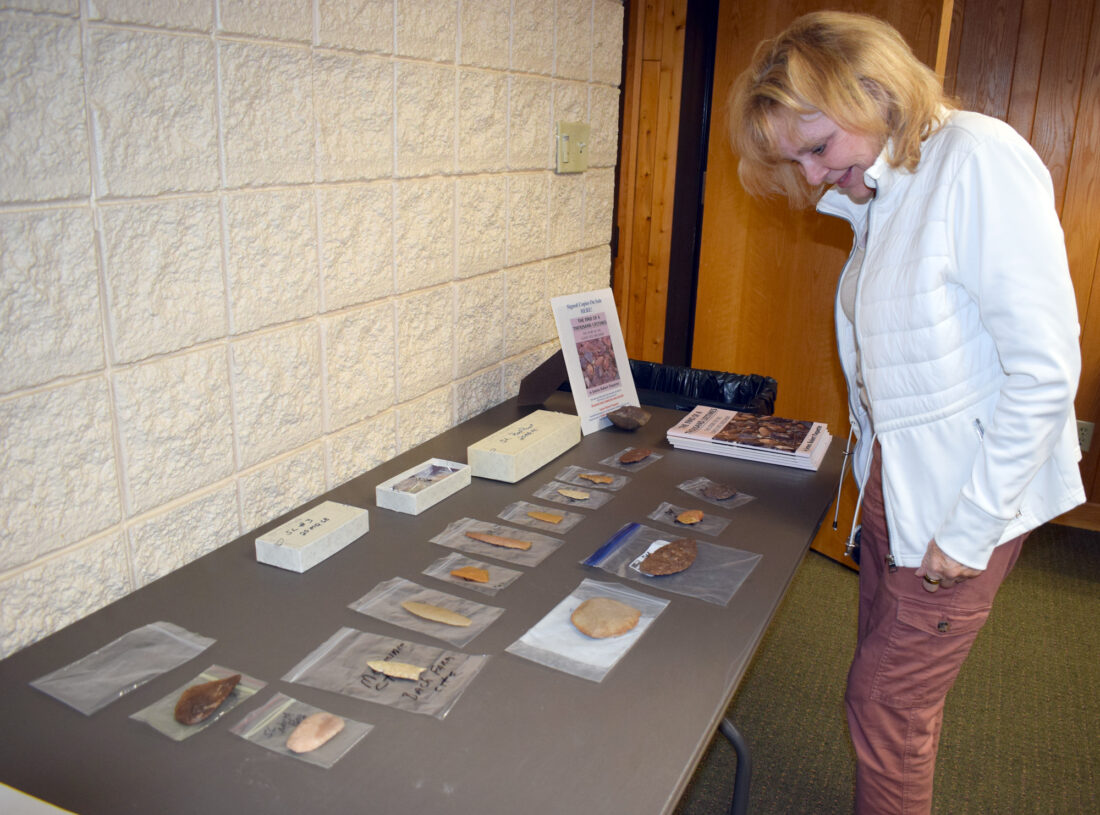

- Meredith Carlson of Spread Eagle, Wis., looks at artifacts brought to an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, Wis. The artifacts are owned by one of the speakers, James Paquette of Negaunee. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

- Kevin Akemann, one of the speakers at an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, looks over a spearhead brought in by Jeff Sternhagen of Fern, Wis. In back is Jim Butler of Crystal Falls. Butler, a retired potato farmer, has found a number of artifacts on his property over the years that he also showed to Akemann. Sternhagen said his grandfather, Carl Sternhagen, found the spearhead on the family farm in 1917. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

- James Paquette of Negaunee, one of the speakers at an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, Wis., shows off a slide of himself and his family just after he discovered his first arrowhead in 1962. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

Meredith Carlson of Spread Eagle, Wis., looks at artifacts brought to an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, Wis. The artifacts are owned by one of the speakers, James Paquette of Negaunee. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

FLORENCE, Wis. — A crowd packed the Wild Rivers Interpretive Center in Florence on Wednesday to learn more about artifacts left by the early people who once roamed through Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula.

The evening featured archaeologists James Paquette of Negaunee, who has served for more than 35 years as an educator and public speaker, and Kevin Akemann, formerly of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee archaeology department.

The event was put on through a joint effort by The Florence County Historical Society and the Northwoods Geology Club, with assistance by Brian and Christine Diel of Diel Insurance Group.

Paquette was among the archaeologists who first discovered Paleo Indian sites near Marquette, proving there were people in the area 10,000 to 13,000 years ago.

Major archaeology periods are divided into several study periods. The pre-contact periods include Paleo Indian, from the end of the Ice Age, 13,000 to 10,000 years ago; Archaic Period, 10,000 to 2,500 years ago; Woodland Period, 2,500 to 400 years ago; and Proto historic, which is about 1600 to 1650.

Kevin Akemann, one of the speakers at an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, looks over a spearhead brought in by Jeff Sternhagen of Fern, Wis. In back is Jim Butler of Crystal Falls. Butler, a retired potato farmer, has found a number of artifacts on his property over the years that he also showed to Akemann. Sternhagen said his grandfather, Carl Sternhagen, found the spearhead on the family farm in 1917. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

One thing Paquette noted was all the rock used to make the artifacts he found came from areas in Wisconsin, indicating the people were nomadic. Artifacts are those made or modified by humans.

“One of the things we wanted to do was to really draw attention to the fact here in Florence County — obviously people have found things — we don’t really know a lot about the pre-history because not a lot has been found here and it hasn’t been documented here as it has in other parts of the state and the Upper Peninsula,” he said.

“You haven’t had people out there like me who have been dogging it for the past 40 years trying to find those things and trying to document those things,” he said. “So what we wanted to do was to get people here to talk about the archaeology of this county, which is a really exciting thing. We wanted people who have ever found things to bring them to try to identify what those things are.”

He found his first artifact, an arrowhead, as a kid in 1962 at Peminee Falls on the Menominee River. Paquette said he has been identifying stone artifacts for 40 years — and some that fall short.

“It’s hard to tell that person ‘it’s just a rock,'” he said.

James Paquette of Negaunee, one of the speakers at an archaeology presentation Wednesday at the Wild River Interpretive Center in Florence, Wis., shows off a slide of himself and his family just after he discovered his first arrowhead in 1962. (Marguerite Lanthier/Daily News photo)

“In order to identify stone artifacts, it’s important that you understand the stone tool flaking process,” he said.

Flakes are the most common artifact on any cultural site, along with core stones, hammer stones and anvil stones used in toolmaking. The flaking material is also known as debitage. He said to a lot of collectors, it’s all waste product and they don’t collect it.

“If you’re an archaeologist, that’s very valuable. You save every little piece, because they have a story to tell. The reason is, it’s the material — where is the material from?” he said.

Broken tools are another artifact commonly found at sites, which Paquette calls “dammits.”

“When you’re making stone tools and you’re trying to whack away, trying to make something, you’re going to get lot of tools that are broken in the manufacturing process,” he said.

Tools can be bifaced — flaked on both sides — or unifaced — only on one side. Those are usually used for cutting purposes.

Scrapers are the most common tool found on sites, he said.

“Individual artifacts are important but what’s more important is the assemblage of all the artifacts that are found on a site. The reason you do that is you can more accurately date the site,” Paquette explained.

Projectile points are the tips used for weapons and they have changed over the years depending on the animal being hunted. In the Paleo period, it would have been mammoths, so the tips were heavier and fatter. As the prey became smaller, the points became thinner and longer, as spears where thrown instead of being thrust into the animal. Arrow points didn’t appear until about 2,000 years ago.

“They changed and they changed rather dramatically over a relatively short period of time,” he said.

Tools were often refurbished and eventually became domestic tools.

Fire-cracked rocks are another common find at sites and is the top way to identify where a campsite was, Paquette said.

“The thousands of generations of people that lived here, they didn’t leave any notes or books, they didn’t leave anything to help us understand who they are,” Paquette said. “The only thing they left behind was these artifacts, so what we have to do is keep track of those artifacts and, in a sense, listen to them. If you understand, they will talk to you. They will tell you how they lived.”

He added, “That’s one of the reasons we’re here tonight — to try to preserve our past here and we know they’re here, so we identify those things, we’re all one people.”

Akemann is a project manager and research specialist who has worked in 67 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, he said.

“Unfortunately there’s a lot we don’t know (about Florence County),” Akemann said. “Florence was the 64th county of the 72. It was created in 1882 from parts of Oconto and Marinette counties.”

For now, it has no known paleo sites, he said. Three archaic sites have been identified — one in Spread Eagle and two by the Long/Fay lakes area. Seventeen Woodland sites have been found, many of these on top of one another, indicating people traveled to the same places.

Wisconsin’s archaeology society is among the oldest in the nation. Charles Brown, one of the earliest directors, reached out to landowners and put advertisements in papers for people to send him artifacts, Akemann said.

They know more about the western half of the state, because of the Nicolet forest, than they do about the east half, he said.

“There hasn’t been a lot of effort to investigate upper Wisconsin,” Akemann said.

A lot of archaeology work is related to cultural resource management — road projects, Department of Natural Resources wetland mitigation, or land trades or utility corridors for power, fiber or gas.

He explained that any project must have an environmental impact survey completed, which includes a cultural impact study. Archaeologists are so busy completing these they often don’t have time to conduct archaeology digs elsewhere.

He briefly explained the history of how cultures developed and changed, with a lot of it being shaped by the environment. When the environment was not conducive to large animal, they moved on.

When the environment started to stabilize, they were able to better predict the seasons. They started to make less trips and occupy the land year-round. Copper began to become more common. Food sources changed. The way they traveled changed. What they cooked in changed.

He said only about 2% of the state has been surveyed.

“This is why we need to reach out to landowners in order to find these things, otherwise we’ll never know,” Akemann said. “So much has happened and so much has changed over time. There’s so little we actually know. There’s so much we could know but we haven’t encountered it.”

One reason they were able to identify items around Marquette was much of the land is privately owned, Paquette explained.

“Where we made all the discoveries were undeveloped lake beds and rivers systems,” he said.

After the event, several people had artifacts to show Paquette and Akemann. Jeff Sternhagen from Fern had a spearpoint believed to be several thousand years old. He said his grandfather, Carl Sternhagen, found it on the family farm in 1917 when he was a boy. Sternhagen said he eventually would like to donate it to the interpretive center for display.

Brian Diel thought the event was fantastic. “It seems everyone’s excited and we’re hoping we will learn some thing that we didn’t know before,” Diel said.

Florence County’s monthly Outdoor Education programs are sponsored by the Friends of the Wild Rivers Interpretive Center and University of Wisconsin-Extension Florence County. Wendy Gehlhoff, director of the center, said this was most well attended program they’ve had.

———

Marguerite Lanthier can be reached at 906-774-3500, ext. 85242, or mlanthier@ironmountaindailynews.com.